Early kings: the French possessions

Much of the drama of Shakespeare's history plays comes from the continuing battle of the English kings to retain or regain posessions in France. When Henry V decided to assert a claim to the French throne, he was reopening a conflict that had continued off and on since William of Normandy conquered Anglo-Saxon England (1066).

Henry V, for example, is convinced by the Archbishop of Canterbury* that his claim to the throne of France is legitimate, and thus sets in action the skirmishes that led to the battles of Harfleur and Agincourt (see 1.2.33ff).

How it all began

Under the Norman and early Plantagenet (or Angevin*) kings, England was only a subsidiary part of a continental dominion ruled by a French aristocracy, at its greatest extent including all of western "France" (see map).

A combination of military prowess, shrewd diplomacy, and efficient administration enabled English kings to maintain their holdings in France for almost 150 years; but King John's incompetence caused the loss of everything except parts of Aquitaine.

John's reign marked the end of the Angevin "empire," and the years from his death (1216) until the reign of Edward III brought a continual chipping away of remaining territories. After unsuccessful attempts to regain Poitou in 1242, Henry III renounced his claims in France and paid homage to the French King Louis IX for the fiefs of Aquitaine and Gascony.

Subsequent English claims in France*.

Footnotes

-

A convenient distraction

The Archbishop, however, is being somewhat machiavellian, for he wants to distract Henry from passing an act of Parliament that would reduce the possessions and revenues of the Church. Henry had also had advice from his father to "busy giddy minds/With foreign quarrels" (Henry IV, Part Two, 4.5.213-14).

-

The Angevin kings

The Angevins originated (as the name indicates) in the province of Anjou, now part of modern France. The English branch began with Henry II, and ended with the death of Richard III.

-

The Hundred Years' War

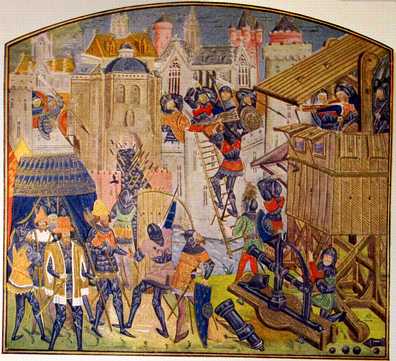

When the last of the Capetian dynasty of French kings (Charles IV) died heirless in 1327, Edward III became the closest male in the line of succession; but his claim was passed over by French nobles in favour of Charles' cousin, Philip of Valois. The argument was over the application of the "Salic Law," the condition that the royal line could not descend through females. (The issue is debated in Henry V, 1.2.33ff.) The matter rested uneasily until Philip's support of the Scots and his seizure of Gascony led Edward and his son, the Black Prince, to invade France. Despite some impressive victories, by the end of his reign English holdings in France were reduced to the coastal areas around Calais and Bordeaux.

Edward III's invasions of France began a long period of conflict, the Hundred Years War (1337-1453), during which the technology of warfare developed significantly, and the need for funds gave increasing authority to the English Parliament (which alone could approve additional taxation). Henry V took up not only Edward III's claim to the French throne, but also claimed his ancestral rights to Normandy and Anjou. These claims were not finally relinquished by English monarchs until the 19th century.